Why was I crying? At that very moment, I realized that that sense of wonder, awe, hope, and excitement simply doesn't exist anymore for kids growing up in our society.

Of course, I might be wrong. In fact, I HOPE I'm wrong. I just worry that our new information-based culture doesn't breed that wonder anymore.

Now you might ask why we need that wonder, why being able to find the answers to all our questions online (or what we think are all the answers) is a bad thing.

1. Sure we can find all the answers to our questions. But what questions are we asking?

There is a lot of material out there about how our current culture is building "tribes" of people over the Internet. So while we have access to all the information the world has to offer, we are selectively turning our attention to just a few tribe-minded things. The Fox News tribe won't necessarily interact with the Daily Show tribe, the Christian Science tribe won't foray into the Atheist tribe, and so on. You can probably see the problems that this causes. Interactions between these tribes are getting more and more heated because ideas are bouncing back and forth within them and gaining support, like a positive feedback loop. As a result, we are getting tribes that not only avoid the information and culture of other tribes, they are actively disdainful of them. "How DARE you question my beliefs when my WHOLE TRIBE agrees with me?" With each negative interaction that occurs, our curiosity about things we don't know outside of our tiny little tribes fades. We not only stop asking questions about things we don't know, we stop recognizing they exist.

2. We don't learn things we don't already know anymore.

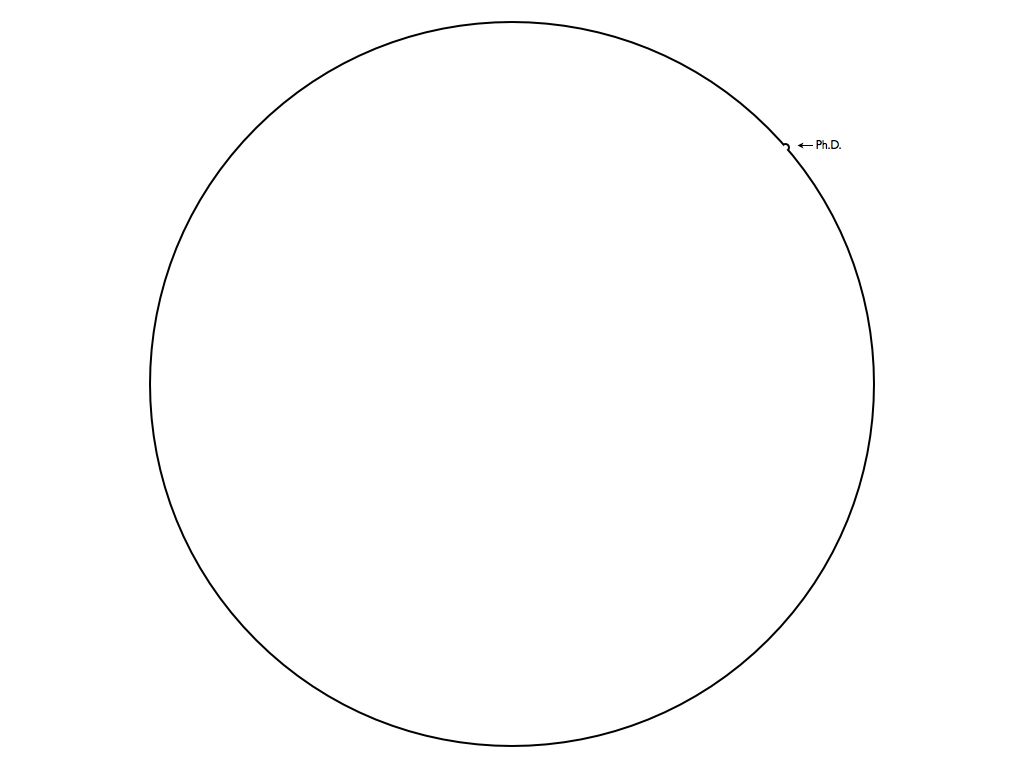

Nowadays, we get to pick through the information that we seek out or gets delivered to us. For instance, most of my news feeds involve neuroscience, STEM education, and art in some capacity, usually from sources that I know very well. These are busy feeds, and I usually have more than enough information to process, which leaves little room for anything else. I don't have the energy to seek out other topics like anthropology, archaeology, religion, food, or politics. But when it comes down to it, I SHOULD be seeking out those other topics; I know quite a bit about neuro, STEM, and art...I know next to nothing about those other topics. I can learn a lot from seeking out those other topics. But I don't. So I get to know a lot about a few topics reported from certain sources, and because I'm so full of information by that point, I think I know it all.

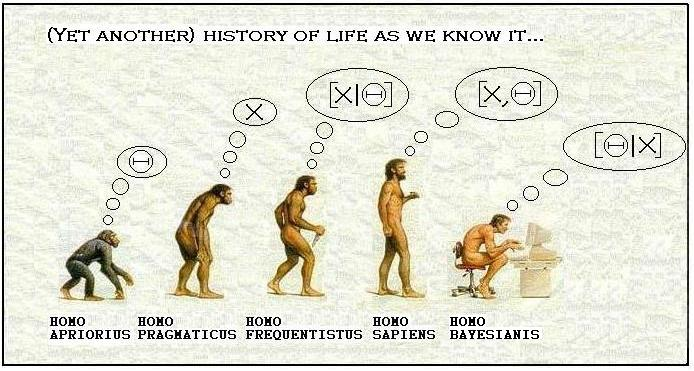

3. We've become arrogant motherf*ckers.

Because when we know everything we think one needs to know, why not be a little proud of it? When all the information that is going to be found forever has been found and just needs to be spread around, the true glory resides solely in reporting. Who cares that the bar for the value of information has been lowered? When you are the one who got to a piece of information that your tribe values first, you WIN. When you make a video of your cat that goes viral, you WIN. When you make up the "Y U NO" meme, you WIN. Having seen many examples of this very thing, the only way we care to contribute to our society is being famous through the least amount of work possible.

4. We have very little to look forward to because we see our world falling apart.

I think that we'd all agree that the political atmosphere of the U.S. is massive disaster; politicians are so far removed from their constituents and so far in the pockets of lobbies and PACs that they often hold conflicting views (even individually) based on whoever is funding their campaigns. The voices of the extremists are becoming more and more audible (thanks, again, to the tribes of the information age), and it seems there's no place for reason or a median voice. As a result, ours is a country that struggles to get anything done when it comes to the ruling body. If the people we put in charge can't get anything done, what's the point of hoping that we can, or holding on to dreams?

All of this factioning, fighting, arrogance, willful ignorance, and exclusivity does nothing but kill wonder. Why wonder about anything if it's going to scare, shock, and maybe even anger me? Why bother to dream when we have all the information about whether that dream is even possible right here in front of us? Why dream of doing anything cool when nobody in MY tribe does anything different than I do, so clearly there's no such thing? What is left to explore that someone I don't know hasn't already explored and become the definitive authority on? Why make the effort to accomplish anything when you could be famous by doing nothing? And why bother, when your hopes get dashed by the ruling body of your country?

So it all comes down to one gigantic concept. MOTIVATION. We are not motivated to seek out new information outside of our tribes. We keep going to the same sources because there is just so much out there. So all of our already-held notions of what we personally and what we as a society are capable of are basically repeatedly validated for us, and we don't want anything else. We don't try because we think there is no point. When the late Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, none of us knew that was possible. None of us knew that humans could do that. And when we all saw it happen in front of our eyes, we started to dream of everything else we could do, stuff that we hadn't even begun to explore.

You can blame science all you want - science brought us the Internet, science made us skeptical of extraterrestrial life, and science killed the hope of magic wands and wizardry and vampires. But it also brought us the space shuttle. It brought us Neil Armstrong. It brought us Curiosity. And it'll bring us the next thing that will open our eyes to a world we didn't think existed. We just need to keep our eyes open.

I mean it. Open them up.

Seriously. Keep them open.

And watch some Doctor Who while you're at it. Wonder about Daleks or something.